|

In 1685, the Roman Catholic James II came to the throne of England.

His agent Richard Talbot, Earl of Tyrconnell, started to dismiss Protestant officers from the army in Ireland, replacing

them with Roman Catholics. For English Protestants, the last straw came when the birth of a son to his second wife meant that

his Protestant daughter Mary would not succeed to the throne. In the summer of 1688, a group of seven English notables sent

a message inviting Mary's husband, William of Orange, to take the English throne. William sailed to England with a formidable

army of 15,000 men, and landed at Torbay in November 1688. James fled to France, but then came to Ireland in March 1689, with

the hope that he could regain the throne with the help of supporters in France, Ireland and Scotland.

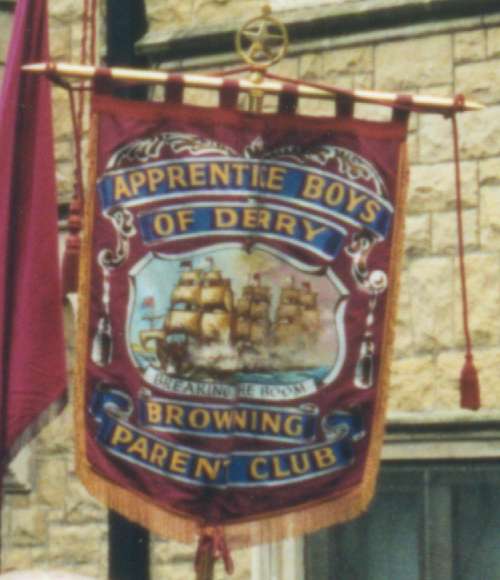

Apprentice boys

In December 1688, the people of the city of Londonderry had been

faced with a dilemma. Tyrconnell had ordered a Catholic regiment (Lord Antrim's

Redshanks) to take over the garrison, replacing Mountjoy's regiment which had been sent to Dublin. Protestant fears of

a repetition of the 1641 massacres appeared to be confirmed by a hoax letter, discovered in a street in Comber, Co.

Down. This anonymous letter warned that Irishmen were going to "murder man, wife and child" on the 9th December 1688.

However, as Bishop Hopkins pointed out, James was still the lawful king and to resist his soldiers was rebellious act.

On 7th December 1688, when the first companies of Redshanks had crossed

the Foyle by ferry, a group of young apprentices took matters into their own hands by closing the gates of the city. A compromise

was eventually reached, allowing two Protestant companies of Mountjoy's regiment to return to Londonderry, to supplement six

companies raised by the citizens themselves. Lieutenant-Colonel Robert Lundy, a Scottish episcopalian, was appointed

as military governor, and he started to improve the defences of the city to meet a likely Jacobite attack.

By April 1689, only Londonderry and Enniskillen had yet to fall to

the Jacobites, and prospects looked bleak when Lundy's troops had to retreat from a battle near Lifford. When he arrived back

at the city, Lundy refused to allow reinforcements from a relief fleet to join the garrison. On 18 April, James II arrived

at the city, apparently unaware that terms for surrender had already been discussed. Suspecting betrayal, the defenders opened

fire, killing one of the King's party.

The citizens had by now decided that Lundy was either incompetent

or sympathetic to the Jacobites, so they appointed Rev George Walker and Major Baker as joint governors.

Lundy was allowed to escape from the city, disguised as a common soldier and carrying a bundle of match. The 105 day siege had begun.

Breaking the Boom

At the start of June, a wooden boom had been constructed across the

Foyle to prevent ships arriving to relieve the city. On 8 June, the warship Greyhound made an attempt to approach

the city, but ran aground and came under fire from Culmore fort. As this ship returned damaged to England, the rest of the

fleet, with troops commanded by Major-General Kirke, did not attempt to break the boom. Instead some ships sailed

to Lough Swilly to land on Inch Island. The boom was protected by some of the Jacobite artillery, and presented a formidable

obstacle in the difficult conditions of the Foyle.

Eventually, on 28 July, three merchant ships called the Mountjoy,

Phoenix and Jerusalem sailed towards the boom, protected by the frigate Dartmouth. The Mountjoy hit

the boom, but rebounded and ran aground. Sailors in a longboat from the Swallow also reached the boom and attacked it with

hatchets. The Mountjoy fired its guns at approaching Jacobite troops, and the recoil helped to refloat the ship. The boom

was broken, and the Phoenix and Mountjoy were able tie up at the Shipquay to unload their precious cargo of food for the starving

people of the city. By the evening of the 31 July, the Jacobites could be seen burning their encampments and marching off

towards Lifford.

|